|

As the 1960's drew to a close and the 1970's began, the baby boom

generation grew up and started looking at things in different ways than

past generations. They had begun

to question everything in the world around them including man's impact

on nature. Environmental

awareness came to the forefront with an awareness of the mistakes of the

past and their impact on the land, water, plants and animals. Pollution

and the decline of cities combined with the increased mobility of the

automobile culture and subsequent creation of the Interstate Highway

system gave rise to theme parks. Just as theme parks were an evolution

from the dirty, old traditional amusement parks, zoos would also

transition during this time

going from concrete and steel cages to more natural habitats as people

began to realize that the animals deserved better treatment and more

natural and realistic habitats.

Taking the zoo concept and

turning it on its head, drive through safari parks allowed the animals

to run free while the humans were in the cages. The animals would be

free to roam larger areas than they ever could in zoos, and habitats

more closely resembling their native homes could be created.

Several companies jumped into the drive through safari business

following a formula of animals with similar geographic origins

cohabitating in fenced in areas separated by gates.

This allowed cars to flow along winding roads while animals

interacted with each other as well as with the passing vehicles.

Throughout the U.S. and other

countries these safari parks opened with varying degrees of success.

Some, like the Lion Country Safari parks were opened as part of theme

parks. The marriage of the safari concept and the theme park concept

proved to be a winning combination.

|

|

|

|

|

Map of World of Animals

Like Great Adventure's Safari, the meandering

roads took motorists through various habitat areas.

Some of the

animals from World of Animals were brought to Great Adventure.

|

|

|

|

|

The elected officials of Jackson

Township and Ocean County were looking to bring in new economic

development in the early 1970's and looked to the success of safari

parks as a potential tourist attraction for the largely rural area on

the western edge of the township and county. In West Milford New Jersey

the Jungle Habitat safari park which had been developed by Warner

Brothers was proving to be a success, drawing thousands of tourists to

the small town and boosting the local economy and Jackson Township and

Ocean County officials wanted to tap the same tourist market with the

ideal location midway between New York City and Philadelphia with easy

access via the Interstate Highways.

Stanley Switlik was one of the

wealthiest businessmen in Jackson Township, and owned more than 2000

acres of beautiful unspoiled woodlands with a series of manmade lakes.

Switlik had made his fortune supplying parachutes to the military during

World War II and lived in a large house near the center of the tract of

land. Working with local officials to help spur development of the area,

he offered to sell more than 1000 acres of land for the construction of

a safari park. Initially speculation was that Warner Brothers were

interested in building a second Jungle Habitat on the site, but another

developer had a bigger vision.

Warner LeRoy never did anything

by half having grown up as part of Hollywood royalty. He believed

anything was possible and wanted to create something spectacular.

He joined with the Hardwicke Group, developers of other Safari

parks in the U.K. and Canada, though nothing on the scale of what Warner

LeRoy had in mind for Great Adventure.

|

|

Warner LeRoy in partnership with

Hardwicke entered into an agreement with Stanley Switlik to purchase the

land to build Great Adventure. After the agreement had been made, plans

were drawn up for "Maxwell's Adventure", building on the success of

LeRoy's "Maxwell's Plum", which had become one of the hot dining spots

in New York City. As the plans

for the park were revealed, Stanley Switlik balked at completing the

land sale, claiming he had committed to the sale only for construction

of a safari park and took legal action to block construction of the

theme park. Legal wrangling delayed construction until finally the

courts found for Great Adventure and the construction of the park began

behind schedule.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Before any construction began on

the Safari, detailed topographic studies of the property were conducted,

mapping the natural hills and features of the terrain. Animal habitat

experts were brought in to study the property and determine how to best

use the land to create the most natural habitats for the animals as well

as preserve the natural beauty of the land.

Preserving the trees on the site was one of Warner LeRoy's main

focuses, and before any

clearing was done careful planning was done to remove the fewest trees

possible during construction.

Several areas were cleared to

create grassy plains for the grass eating animals, and small ponds were

created in several locations to create watering holes for the animals to

drink and bathe. The 6 miles

of 3-lane road were cleared and paved and a the barn facilities to house

the animals were constructed in the center of the Safari along with

veterinary facilities and other support buildings along the northeastern

edge.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Each section also featured small

shelters for the animals along with feeding bins of different shapes and

sizes as well as other habitat elements.

The shelters were almost all identical, with a simple steel frame

supporting a pitched roof. The

removed trees supplied the log siding for the various structures.

Feeding bins were tailored to the

needs of the animals with varying heights and sizes to match the

animals in each section. Other elements added included rocks and

boulders which were trucked in from quarries in Pennsylvania and

northern New Jersey, logs and other "play" structures for the big cats

and concrete pipe sections that were set into the hillsides to serve as

dens for the bears.

The entire Safari was surrounded

with strong chain link fences. In many areas the fences extended below

ground to prevent animals from digging under and with the really

dangerous animals like the big cats and bears, metal panels were

attached to the tops of the high fences, preventing the animals from

climbing over the top. The

metal panels were painted green to help make them blend in with the

thick forest behind them and make them less obtrusive.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

To control the flow

of cars and keep the dangerous animals like the big cats and the bears

contained, a set of lock style gates were constructed at the ends of the

section. To control the gates a pair of octagonal gatehouses on stilts

were built, offering the attendant a clear view of the entire lock

section to ensure that the animals were not hiding between the cars. A

group of cars would be let into the lock and the gate closed behind

them, then the gate at the forward end would open when the area was

clear. The four gates were electrically powered, unlike the gates

between the other animal sections which relied on a human attendant to

shoo the animals back into their own sections.

|

|

|

Construction of the park was a

massive effort with thousands of workers all over the property working

long days and nights to get everything ready for the July opening.

Originally the opening date was slated for June of 1974 but with the

construction holdups caused by the legal battles over the theme park the

bulk of the work did not begin until January of 1974. The completion of

the park in six months was a herculean effort. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The plains of the Safari were

covered with top soil to support growing grass in the sandy native

earth. Since feeders were constructed for the grazing animals, the grass

was primarily intended to be decorative, but the animals' instincts to

graze meant that the grass would often be stripped leaving the plains as

a more desert-like environment.

Once the facilities were in

place, the animals began to arrive to get acclimated to their new homes. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| Some of the Safari's animals came

from existing safari parks, farms and zoos. Most of the herd animals

were relocated from parks in Canada and were used to the cold climate

and though still wild, were used to varying degrees of interaction with

humans. They tended to adapt easily to the new park and the acres of

land they were free to roam. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

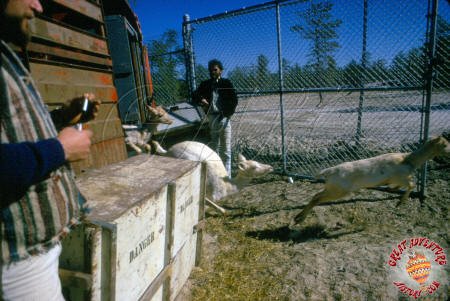

The herd animals like the

gazelles and ibex here relatively easy to handle and move into the

Safari, and the staff could simply open the gates of the animal carrier

trailers. The big cats, bears and other dangerous animals required

special handling in reinforced crates. The crates could be placed at

doors built into the back of the animal shelters and using a remote

cable the doors could be opened with the handlers a safe distance away. |

|

|

|

Once a crate was placed at the

door to the shelter the end of the crate would be opened as the

counterweight was pulled to raise the metal door. The animals could then

wander into their new enclosure and the door would close behind them. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

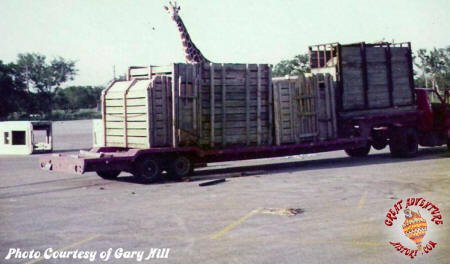

The transporting animals to the Safari created

unique challenges. With the height, weight and danger involved the

transport vehicles were unique and often were a spectacle as they drove

to the park. Many of the animals were accustomed to interacting with

people

|

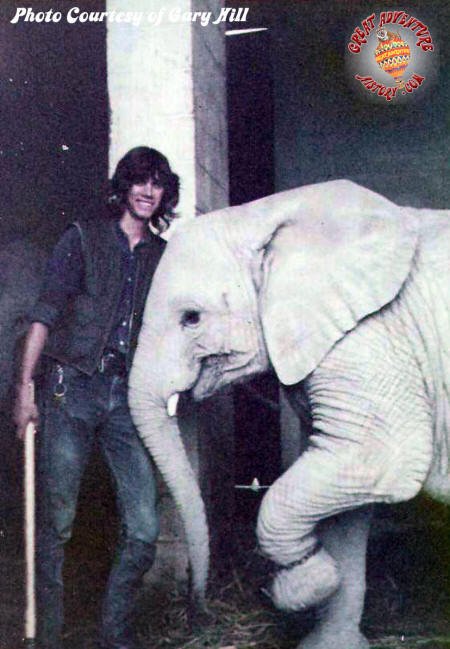

The Safari's elephant herd was

brought to the park directly from Africa. An expedition was sent to

Africa with the goal of finding and capturing a herd and then

transporting the animals across the ocean to New Jersey.

Once

the animals had been rounded up and loaded into containers, they were

loaded onto planes flying from Africa to a stop over in Europe, then

onward to Kennedy Airport in New York where they were loaded onto trucks

for the final leg of their long journey.

Once at the park, the

herd quickly adapted to their new surroundings and their human keepers.

Those original elephants still live at the park today, along with their

offspring that have been born and raised at the park over more than 35

years.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

One of the most familiar aspects

fo the Safari has always been the ubiquitous striped vehicles used by

the wardens. As the animals became more familiar with their new homes

they quickly began to recognize the zebra striped vehicles since they

usually appeared with their food. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

At the entrance to the Safari the gate structure took shape. Four

two-sided ticket booths were constructed to handle up to eight lanes of

traffic. The booths were connected with a truss framed roof structure

providing protection from the weather. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Along with the construction of

the entrance plaza and associated facilities, final preparations for

opening day included running the wiring for the FM transmitters down the

center of the road to provide the narration for each section. Once the

wires were laid, the three lanes of pavement were added. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When July 1st rolled around, the Safari opened to the public and was as

big an attraction as the Enchanted Forest theme park. Film crews often

toured the Safari, showing off the world's largest drive through safari

park. Guests lined up to take the 6-mile drive, and with many cars

overheating in the heat of the day, requiring the Safari's wardens to

provide assiatnce to the stranded motorists.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

![]()

![]()